Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) presents itself as a science of precision. Its authority in autism services rests on a familiar promise: careful measurement produces objective truth, and objective truth produces effective care. Yet when you examine what sometimes qualifies as doctoral-level research in this field, the object of study can quietly shift. The child disappears. Learning disappears. Autism disappears. What remains is the stopwatch.

Consider a 2019 doctoral dissertation from Western Michigan University titled A Component Analysis of an Electronic Data Collection Package. Its author, Cody Morris, identifies a technical problem within ABA practice: caregivers do not always record behavioral data “on time,” and these delays may “adversely affect treatment decisions.” The proposed solution is not to question the demands placed on caregivers, the meaning of the data being collected, or the validity of the behaviors selected for measurement. It is to engineer stricter compliance with data entry.

This dissertation is not about improving children’s lives. It is not about development, communication, autonomy, or distress. It is about whether an adult enters information into a spreadsheet within five seconds.

And this, in ABA, is defended as science.

The Study, in Plain Terms

The experiment involved three adults: two parents and one direct-care staff member, all supporting children who were receiving home-based behavioral consultative services for what the dissertation describes as “severe problem behavior.” The children themselves are not identified as participants. They are not described developmentally or diagnostically. They exist only as sources of behavior to be logged.

Each caregiver was instructed to select daily recording periods—up to forty minutes per day—during which the child was present and likely to engage in target behaviors. Crucially, caregivers were told to ensure that another adult was available to assist the child so the caregiver could avoid “distraction” and focus exclusively on data input.

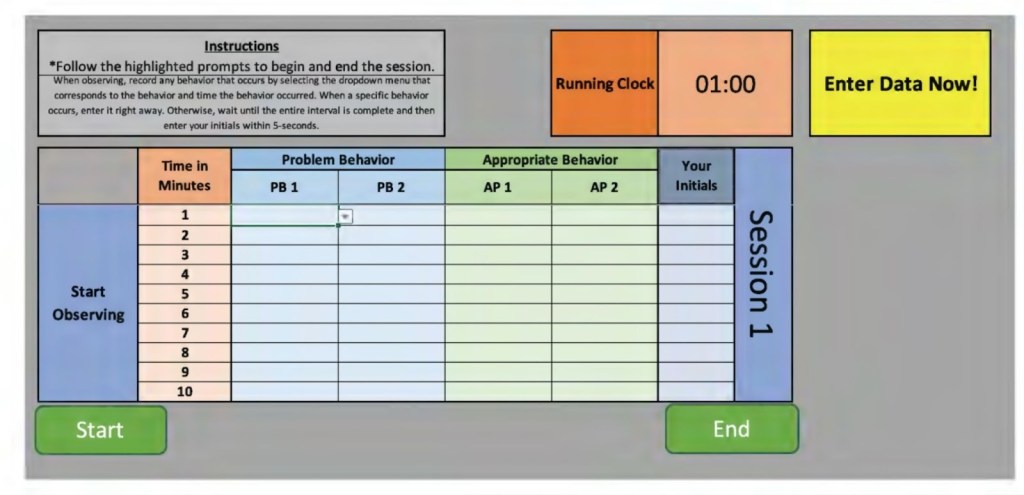

The task was rigidly defined. Using a laptop running an Excel-based electronic data collection system, caregivers recorded whether specific behaviors occurred during one-minute partial intervals. If a behavior occurred, it was to be entered immediately. If it did not, the caregiver was required to enter their initials within five seconds of the interval ending. Any entry earlier or later was scored as incorrect.

The outcome that determined success or failure was not child behavior, caregiver understanding, or quality of interaction. The dependent variable was the timeliness of data entry.

What’s Autism got to do with Behaviorist Experiments?

Across the body of the dissertation, the word autism appears only once—and only as a hypothetical example of a setting where data collectors might work. It is presumed that if you are a parent of a child who was referred for ABA due to severe behavior problems, then likely it is due to an autism diagnosis. There is no diagnostic information about the children. Autism is never defined, discussed, or analyzed. No autism outcomes are measured.

Autism functions here, as a buzzword backdrop. Consistent in behaviorist scholarship is the unspoken justification for why this research matters. Autism, the condition, is the driver of their academic experimentation, even when the research bypasses autism in its entirety. The work exists squarely within the ABA ecosystem that markets itself as the “gold standard” of autism intervention, despite containing essentially no autism science.

The “interventions” tested in this dissertation are not therapeutic strategies. They are interface controls—tools designed to regulate adult behavior in much the same way productivity software monitors employees. Measuring the technical savviness and computer productivity of a caregiver has no translational value to an autism intervention.

The assigned interface and tasks were structured as experimental conditions, and were introduced sequentially:

- A basic electronic data collection sheet with a running timer and dropdown menus.

- Automated on-screen prompts that briefly flash “Enter Data Now!”

- End-of-session feedback showing percentages of on-time versus late entries.

The results show what any behaviorist would predict. Immediate feedback works best.

One caregiver’s on-time data entry improved from roughly fifty percent at baseline to over ninety percent when specific interval feedback was introduced. Another improved from fourteen percent to near perfect compliance. In the discussion section, Morris acknowledges something revealing: caregivers may have been influenced not by improved understanding, but by social pressure. The investigator was also the clinician overseeing their children’s services. Participants reported wanting to know “what the investigator thought” of their performance.

In the analysis of the dissertation, the participants were referred to with pseudonyms such as “Steve,” “Lindsay,” “Molly,” and “Chris.” Late and early entries were simply coded as “not entered on-time.” Under these conditions, Christine entered only 36 percent of intervals on-time when problem behavior occurred. Lindsey entered 69 percent. Steve entered 47 percent.

Morris then modified the feedback condition. Graphic feedback was presented in the form of a red bar graph, explicitly justified as aversive because “red is commonly associated with negativity or correction in Western cultures.” The effect was immediate. The most telling detail comes not from a graph, but from a participant’s own words. Seeing the red bars, one caregiver said, “It got my butt in gear.” The Morris system worked to influence caregiver’s behavior, by applying aversive cues and authority dynamics to produce faster compliance with a timer.

1. Immediate Interval-by-Interval Feedback (Not Just Red, but When)

The single most effective manipulation—across participants—was immediate, specific feedback delivered after every one-minute interval, not delayed or summary feedback.

In this condition, caregivers received:

- A graphic display after each interval

- A running percentage of “on-time” vs “late/early” entries

- Visual comparison between correct and incorrect performance

This mattered more than whether the feedback was positive or negative, because it collapsed the temporal distance between error and correction. The caregiver no longer had space to drift, multitask, or interpret their own performance. The system did the interpretation for them.

In behaviorist terms, this is classic:

- Immediate consequences > delayed consequences

- Continuous monitoring > periodic evaluation

In human terms, it is surveillance, not support.

2. Prompts That Functioned as Compliance Cues (“Enter Data Now!”)

Another manipulation that increased timeliness—though less reliably than immediate feedback—was the introduction of automated on-screen prompts, typically flashing messages such as:

“Enter Data Now!”

These prompts did not teach anything. They did not clarify expectations. They did not reduce caregiver burden. They functioned as external control signals, reminding caregivers that the system was watching and that action was expected now, not later.

Interestingly, prompts alone sometimes produced worse performance initially (as with Christine), suggesting that reminders without consequences can increase pressure without improving accuracy. It was only when prompts were paired with feedback—especially feedback that signaled error—that performance stabilized.

This mirrors what we already know from coercive systems: pressure creates stress; pressure with consequence creates compliance.

3. Investigator Authority and Social Evaluation

One of the most important variables in the study was never formally graphed, but Morris acknowledges it explicitly in the discussion.

The investigator:

- Was also the clinician overseeing the child’s services

- Reviewed caregiver performance

- Controlled which components would remain in the final “package”

In behaviorism, “components in the final package” refers to the process of refining an intervention by determining which parts were essential for producing meaningful behavior change. Initially, multiple procedures or strategies—such as prompting, reinforcement, or feedback—may have been included as part of a larger treatment package. Through systematic evaluation or component analysis, each element’s effectiveness was assessed to identify which ones contributed significantly to the desired outcomes. Based on these results, Morris selected the most effective and practical components to include in the final intervention package, ensuring that it remained both efficient and evidence-based. This process strengthens the treatment’s integrity and feasibility by retaining only the components that are necessary and functionally important. Essentially, the final package is presented as authoritative evidence on how to apply this intervention to practitioners.

Caregivers reported wanting to know:

- “What the investigator thought”

- Whether they were “doing it right”

The caregivers were not interacting with a neutral or purely technical system. Instead, they were operating within a social and power dynamic in which the researcher or professional held evaluative authority. Because of this imbalance, caregivers felt stress and social pressure; their participation and “productivity” were tied to judgments that could affect the services their child received. The most distressing consequence was the risk of jeopardizing the ABA service relationship.

Therefore, the experimental setting did not test a neutral or independent technological interface. It tested a system that existed within a hierarchical, coercive relationship, where caregivers’ behavior was influenced by their perceptions of professional oversight and consequences. The apparent increase in timeliness or compliance cannot be attributed solely to the technology (for example, the red progress bar) but must be understood as a result of the social context—fear of negative evaluation, desire for approval, and concern for their child’s outcomes. In this sense, the “red bar” was effective not because of its design alone, but because it functioned as a symbol of supervision and authority, effectively simulating the presence of a supervisor rather than replacing it.

The investigator’s dual role as researcher and clinician added implicit authority and evaluative pressure. Guided “choice” narrowed acceptable responses to those that produced compliance. Together, these elements formed a closed control loop in which late or early entries became uncomfortable and shamefully visible. The system did not support caregivers in the realities of caregiving; it trained them to respond to a timer. In other words, what reduced late entries was not insight or care, but the systematic removal of autonomy. These are behaviorist tools long applied to children, and now in this dissertation, were redirected at adults and relabeled as research progress.

4. Guided Selection (Choice Without Real Autonomy)

Morris describes the final phase of the experiment as “guided selection.” Caregivers were asked which data-collection components they preferred, but the investigator simultaneously identified which option was the “most effective” based on performance data. Formally, this looks like a choice. Functionally, it is not. A useful way to understand it is to imagine being told you can “choose anything you want” from the kids’ menu at McDonald’s—while already knowing that none of the options meet your dietary needs, and that the adult supervising the order has made it clear which item is expected. The menu exists, but the acceptable answer is predetermined. Any deviation is technically allowed, but practically discouraged.

This is the kind of choice offered here. Caregivers were not invited to reflect on whether the system fit their lives, reduced stress, or made sense in the context of caregiving. They were invited to select from pre-approved options after being shown which one produced the highest compliance. Predictably, they chose the option that aligned with the system’s reinforcement contingencies. What increased timeliness, then, was not caregiver insight or agreement, but acquiescence to a structure in which “preference” meant selecting the least punished path.

A social validity assessment was administered after the component analysis had already identified which features of the electronic data collection system produced the highest levels of on-time data entry. Its function was not to ask whether the system made sense to caregivers, improved caregiving, or felt appropriate in the context of family life. Instead, it was used to assess whether caregivers accepted and preferred the procedures that were most effective at increasing their compliance with data entry demands. In other words, social validity here was not a check on whether the intervention was meaningful or humane. It was a post hoc confirmation that caregivers were willing to go along with the procedures that worked best from the experimenter’s perspective. That is why “guided selection” works here: once effectiveness is defined as compliance, social validity becomes a measure of alignment with reinforcement contingencies, not a measure of meaningful consent or real-world value.

Research Fidelity and Ethics

Throughout the dissertation, timeliness is treated as a proxy for accuracy, and accuracy as a proxy for quality. Faster data entry is assumed to produce better treatment decisions, even though no treatment outcomes are measured. This is a conceptual shortcut with serious consequences. It allows the field to treat procedural compliance as evidence of clinical rigor, while leaving untouched the deeper questions: Are the behaviors being measured meaningful? Are caregivers supported or surveilled? Are children safer, calmer, or more autonomous? None of these questions are asked, because they cannot be graphed in one-minute intervals.

What is praised as “fidelity to the protocol” in social science research often masks a deeper flaw: a commitment to procedure over people. When researchers prioritize strict adherence to design at the expense of participants’ understanding or engagement, they do not preserve rigor—they expose a serious methodological and ethical failure.

In the U.S., federal regulations require that institutional review boards (IRBs) ensure that experimental research involving human participants provides a net benefit. Any potential risks must be clearly identified in the IRB materials. Amy Naugle, Ph.D., a tenured professor at Western Michigan University, approved the research project under IRB project number 18-11-06, designating it as eligible for exemption from certain IRB rules. Exemptions are granted when no human participants are involved, vulnerable populations (i.e. pregnant women, prisoners, individuals who cannot consent) are not targeted, no deceptive strategies are used, and no risks are present. The IRB application must also disclose any potential conflicts of interest. If participants receive no benefits from the study, the IRB may recommend financial incentives, such as gift card drawings.

In the Morris research, all these parameters ensuring participant protection were severely violated, breaching both federal and international ethics standards. Most egregiously, Morris did not identify the children as research subjects, to avoid identifying any harm of behaviorism with vulnerable participants. By targeting the caregivers instead, Morris avoided identifying any potential risk to the aversives, coercion, or deception employed in the experiment. Lastly, by convoluting the net benefit with the service contract of the children’s so-called therapy, the caregivers had nothing to gain but everything to lose. Embedded into this ‘research’ is a call to action for a human rights tribunal, under the Declaration of Helsinki.

Why This Matters

The dissertation includes institutional review board approval and a consent process. Ethics are satisfied procedurally. Conceptually, they are absent. In contrast with social science research standards, the study does not interrogate power dynamics, coercion, caregiver stress, or the moral implications of transforming family members into unpaid data technicians. The children whose existence is being operationalized into binary data, are not considered research subjects at all. Autistic children are background conditions whose experiences, consent, and well-being remain outside the analytic frame.

ABA’s research culture often equates rigor with control, and control with measurement. If the numbers are clean, the method is validated. If the method is validated, the field claims authority. This doctoral dissertation focuses entirely on whether adults respond to a digital prompt within five seconds, while saying almost nothing about autism, development, or human experience. Such misbehavior is emblematic of what it looks like when the field’s definition of “evidence” has collapsed inward. The stopwatch has replaced the child, and behavior of their parent is a weak supposition to autism as a condition that too can be manipulated.

ABA’s dominance in autism policy is justified by claims of scientific superiority. Insurers fund it. States mandate it. Families are told it is the only evidence-based option. Yet the evidence base includes work like this: technically precise, procedurally obedient, and conceptually hollow. The logic is unmistakably behaviorist: prompts, feedback, and performance criteria are used to shape adult behavior. The caregiver becomes the organism. The spreadsheet becomes the environment. Morris’ evidence base for “autism treatment” includes work where the child, autism, and learning quietly drop out of the frame, and the only thing that really matters to this behaviorist is whether an adult clicks a box within five seconds.

Improving data entry speed does not equal improving care. Training caregivers to respond to red bars does not equal understanding autism. A discipline that confuses efficiency with truth, risks becoming what this dissertation quietly reveals it to be: a system optimized for measurement, not meaning. Until lawmakers reckon with what it chooses to recognize as evidence, and what it systematically excludes, policy about autism will continue to measure seconds while missing the substance of human life. What ABA eagerly promotes as “research” is a study where the outcome is caregiver obedience to a timer, not any change in autistic children’s lives.

Read this dissertation:

Morris, C., & Peterson, S. M. (2020). A component analysis of an electronic data collection package. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 40(3-4), 210-232.

Leave a comment