If you are a parent of a child whose behavior has been labeled a “problem” at school, you may already recognize the language that follows. Words like support, independence, evidence-based, self-management, feasible, and appropriate often sound reassuring. They suggest help. They imply care. They are frequently used in IEP meetings, evaluation reports, and consent forms to describe interventions schools say are required by law.

This article asks you to pause when you see that language. Not because every use of it is wrong, but because in some cases it hides more than it reveals. When a study emphasizes measurement, ratings, reliability, and efficiency more than teaching, adaptation, or adult support, it may be solving a school’s compliance problem rather than your child’s needs. When “independence” means your child is responsible for tracking and scoring their own behavior, it is worth asking who that really helps.

You are reading this article to understand what happens when behavior support is quietly redefined as self-monitoring, and when data collection stands in for care. You will see how a well-credentialed study frames itself as helping students while primarily benefiting institutions—and how that framing travels from research papers into classrooms, IEPs, and everyday school decisions. This article is not asking whether the numbers look good. It is asking whether the child is truly being supported.

Introduction: What This Study Claims to Do

Jessica L. Moore’s 2019 dissertation, An Evaluation of the Individualized Behavior Rating Scale Tool (IBRST) in Inclusive Classroom Settings, was submitted in partial fulfillment of a doctoral degree in Applied Behavior Analysis, at the University of South Florida.

The researcher asks whether students can be trained to monitor and rate their own behavior in a manner comparable to adult observers. The IBRST is a Direct Behavior Rating instrument commonly used in school settings to track progress toward behavioral goals. Conventionally, these ratings are completed by teachers or trained staff; Moore’s study investigates whether students themselves can assume this role with sufficient accuracy and reliability.

The study is situated within the legal and policy framework of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which requires schools to provide evidence-based behavioral interventions and supports when a student’s behavior interferes with learning. Moore presents self-monitoring as a promising strategy that may reduce teacher workload, increase student independence, and offer a feasible, cost-effective method for collecting intervention data while maintaining measurement integrity.

Moore reports three primary conclusions. First, she argues that student self-ratings on the IBRST demonstrate high correspondence with observer ratings, supporting the tool’s reliability and validity. Second, she finds that self-monitoring is associated with increased on-task behavior and decreased problem behavior. Third, she characterizes the approach as practical, accurate, and appropriate for use in classroom settings, aligning it with the terminology and standards commonly used to define compliant, evidence-based educational practice under IDEA and related federal guidance.

At face value, the study presents self-monitoring as both a credible measurement strategy and an effective behavioral intervention. However, a closer examination of the study’s design, procedures, and underlying assumptions raises a critical question: while the self-monitoring appears to improve behavior without sacrificing data reliability, does it meaningfully support students’ development? Or does it primarily reduce costs for the schools?

What IDEA Promises vs. What Schools Are Required to Do

IDEA requires that students whose behavior interferes with learning receive appropriate behavioral interventions and supports as part of a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE). In principle, this mandate is intended to ensure that behavioral challenges are addressed through individualized, proactive services that improve access to learning and support long-term developmental outcomes.

In common usage—particularly among parents and caregivers—“behavioral support” generally implies direct assistance to the child, such as teaching self-regulation or coping skills, adjusting classroom environments, providing counseling or therapeutic services, strengthening communication, or offering structured adult guidance. The underlying expectation is that interventions will build capacity, reduce distress, and enhance meaningful participation in school.

Moore’s dissertation adopts the language of IDEA but redefines the focus of support. Rather than centering skill development, environmental adaptation, or relational intervention, the study frames the primary challenge as schools’ limited capacity to collect reliable behavioral data. Within this framing, the proposed solution is improved measurement efficiency rather than expanded student support.

This shift reflects broader institutional pressures. Schools are required to demonstrate that interventions are evidence-based, measurable, and cost-effective, making systems that are inexpensive, scalable, and low-burden for staff particularly attractive. In this context, tools such as the IBRST function as administrative technologies that facilitate legal compliance while minimizing additional resource commitments.

As a result, IDEA’s promise of meaningful behavioral support risks being operationalized as a documentation requirement rather than a substantive intervention mandate. The distinction between supporting students and measuring them becomes blurred, allowing data production to stand in for care.

What Actually Happened in the Study

Moore’s study was conducted at a private school that uses a highly structured instructional model. Students spend most of the school day completing workbook-based academic tasks with minimal peer interaction.

Three students were chosen for the study, each identified by their teachers as exhibiting behaviors that interfered with classroom learning. The students are not described as who they are, but as what they disrupt. Their feelings, reasons, and inner life never appear. This is how the study describes them:

- Danny was a 13-year-old male student referred for participation due to problem behaviors that interfered with academic engagement. Target behaviors included off-task behavior, noncompliance, and verbal disruptions during instructional time.

- Deborah was a 15-year-old female student identified as exhibiting problem behaviors, including talking back to staff, leaving her assigned seat, and verbal outbursts.

- Bailey was an 11-year-old student referred for intervention due to off-task behavior and disruptive verbalizations that impeded classroom instruction.

Participants were trained to use the IBRST to rate their own behavior in two target domains: on-task behavior and problem behavior. During instructional periods, a timer sounded at fifteen-minute intervals. When the timer signaled, each student paused their academic work, recorded a self-rating on a five-point Likert scale, and then resumed their assignment. This cycle repeated throughout the observation sessions.

At the same time, a trained adult observer simultaneously recorded behavioral data using the same rating framework. The student’s self-scores were then compared to the observer’s ratings. The primary outcome measure was the degree of correspondence between these two data sets.

Within this design, “success” was defined as agreement. High alignment between student self-ratings and adult observer ratings was treated as evidence that students could accurately monitor their own behavior and that the IBRST functioned as a reliable and valid measurement instrument in classroom settings.

The Anchor System — Where Individualization Is Claimed

A central claim of Moore’s methodology is that it tailors the IBRST to each student’s behavioral profile. She achieves this by establishing individualized anchors (endpoints and midpoints) for the five points of the rating scale.

In principle, this process was to be collaborative: students were invited to help define what constitutes different levels of on-task or problem behavior on the five-point scale, creating the appearance that ratings reflect each child’s personal experience. For example, “having a very good day” (a 5 on the 1-5 scale) might be defined for one student as having only two problem behaviors per half-hour, but for another student as five problem behaviors.

In practice, however, the anchor-setting was constrained by adult-collected baseline data. Students were shown prior frequency counts of their own behavior and asked to estimate how often target behaviors occur at different rating levels. When a student’s proposed anchor points did not align with the existing data, the discrepancy was regarded as inaccuracy rather than as an alternative interpretation. The student was guided through leading questions, redirected toward values that matched the baseline distribution, or, if agreement was not reached, provided with what the researcher deemed the appropriate anchor definition.

This approach is problematic. The child’s subjective understanding of their behavior is not preserved within the measurement system. Instead, it is adjusted to conform to predefined adult interpretations of what behavioral frequencies should represent.

The individualized anchors therefore do not function as expressions of personal meaning, but as calibration tools designed to standardize how students interpret and use the rating scale.

Where Did the Support Go?

Although Moore characterizes self-monitoring with the IBRST as a behavioral intervention, the study provides little evidence of direct support targeting students’ underlying skills or well-being. Participants were not taught new coping, self-regulation, or communication strategies, nor were sensory accommodations, emotional supports, or environmental modifications introduced to address sources of distress or difficulty.

Instead, the primary change to students’ routines was the addition of a structured self-monitoring task. The intervention was repeated documentation within predefined behavioral categories rather than skill-building, relational support, or contextual adjustment.

Within this framework, behavioral “support” is effectively redefined as self-measurement. Progress is assessed through increased alignment between student self-ratings and adult ratings, rather than through demonstrated growth in emotional regulation, learning conditions, or personal agency. Success depends on the student’s ability to complete the rating process in ways that conform to institutional expectations.

What the Results Actually Show (and Don’t Show)

A. Reported Outcomes

Moore reports three principal findings. First, participating students demonstrated increased on-task behavior over the course of the intervention. Second, recorded instances of problem behavior declined. Third, student self-ratings showed near-perfect correspondence with ratings made by an adult observer, which Moore interprets as evidence of strong reliability and concurrent validity for the IBRST.

On the surface, these results suggest that self-monitoring may both improve classroom behavior and produce accurate behavioral data. Within the study’s analytic framework, increased agreement between student and observer ratings is treated as confirmation that students can effectively monitor their own behavior and that the measurement system functions as intended.

Study Limits & Why the Findings Don’t Generalize

Even on its own terms, Moore’s study has substantial limitations (some of which are acknowledged by Moore) that restrict the generalizability of its findings. The sample consisted of only three students, limiting the extent to which conclusions can be applied to broader or more diverse student populations.

The research was conducted in an atypically controlled classroom environment, where students worked with minimal peer interaction and highly structured routines. Instruction centered almost entirely on workbook-based tasks, a format that may be particularly compatible with timed self-monitoring and simplified behavioral categorization but does not reflect the complexity of most general education classrooms.

The duration of the study was relatively brief (one to two months), and no long-term follow-up data were collected to assess whether observed changes in behavior were sustained over time or transferred to other settings. As a result, the findings cannot determine whether self-monitoring produced durable developmental effects or only short-term procedural compliance.

Finally, the study does not examine whether improvements in on-task behavior or reductions in problem behavior translated into meaningful academic learning. Without evidence linking behavioral ratings to educational outcomes, claims about the broader instructional value of the intervention remain limited.

The Psychological Cost of Self-Surveillance

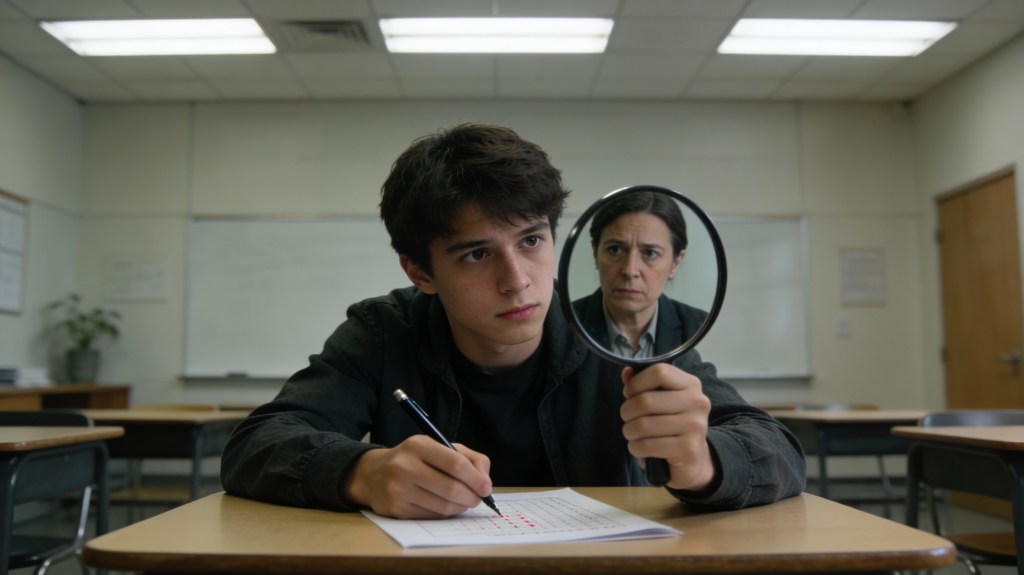

Beyond questions of effectiveness, Moore’s intervention raises concerns about the psychological implications of frequent self-monitoring. Requiring students to repeatedly evaluate and rate their own behavior encourages a shift from external participation toward internal self-surveillance.

Over time, this practice may induce self-vigilance, in which attention is directed less toward learning, exploration, or social engagement and more toward continuous self-assessment against external standards.

A student who must evaluate their behavior at regular intervals learns to watch themselves more than they learn to participate. The timer replaces curiosity with caution. Instead of developing a sense of competence through interaction and exploration, the child develops a sense of conditional safety—safety that exists only when the scorecard is filled out.

This constant vigilance erodes the foundation of identity. Where most children learn who they are by testing boundaries, expressing emotion, and repairing mistakes, the self-monitored child learns that deviation is danger. They internalize the evaluator’s gaze (here, embodied by the scorecard) and become custodians of their own compliance. Over time, this produces not independence but dependency—on systems of scoring, on authority for validation, on the illusion that normalcy can be achieved through perfect data.

Chronic self-surveillance induces a state of low-grade stress similar to the physiological pattern of hypervigilance. The body learns that every interval brings judgment. Even short-term exposure can shape how a child later relates to institutions of power: to doctors, therapists, or employers. When the self is conditioned to accept observation as ordinary, privacy feels unnecessary and scrutiny feels natural.

The adult who once circled numbers on a classroom form may later disclose intimate details to authority without hesitation, accustomed to being scored. The line between care and control dissolves. What began as “behavioral support” becomes the training of citizens who are unguarded before authority.

For these students, the long-term harm is not the mark on a data sheet but the constriction of selfhood. The habit of watching oneself through the eyes of others limits the capacity for self-direction, creativity, and dissent. Under constant measurement, growth is replaced by calibration. The child learns that life is lived inside boxes and that the goal is not understanding, but achieving acceptable numbers. The researcher assumes that this counts as improvement, without asking whether your child learned anything new or simply learned to hold themselves in.

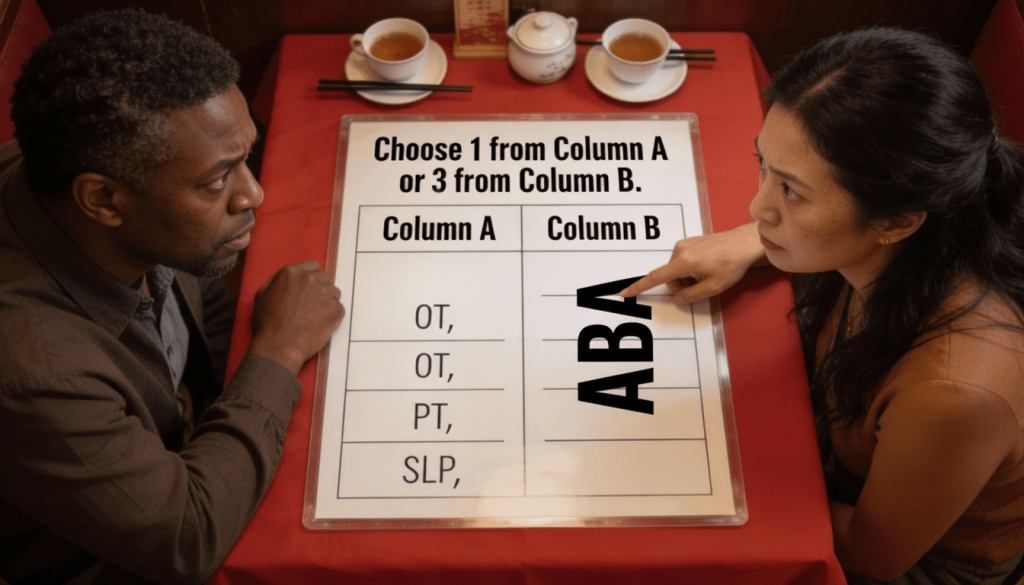

The Institutional Payoff — Why Schools Like This

The appeal of self-monitoring tools such as the IBRST is closely tied to institutional incentives rather than to demonstrated educational benefit. Under IDEA, schools face ongoing pressure to document that students whose behavior impedes learning are receiving evidence-based interventions. At the same time, teachers and support staff carry heavy workloads, and districts often operate under significant budgetary constraints.

Training students to collect their own behavioral data shifts a portion of monitoring labor away from professionals and onto the children. From an administrative perspective, the benefits are clear. Schools obtain quantifiable behavioral data, completed rating forms, and records that can be used to demonstrate legal and procedural compliance with IDEA and FAPE requirements. These materials serve as evidence that interventions are in place, progress is being tracked, and accountability standards are being met.

For the student, the tradeoff is direct and cumulative. Moore’s proposed intervention takes instructional time away from learning and redirects it toward self-monitoring. For the student, as this monitoring becomes accepted as a routine offering, the school can document that an intervention is in place and behavior is being tracked.

At the same time, parents, if they are not seeing any generalizable improvements, can no longer request additional support, because the school has fulfilled its legal burden.

Ethics & Review — How Surveillance Gets Approved

Moore’s study received Institutional Review Board approval at her university under a “minimal risk” classification, reflecting a framework in which risk is primarily defined in physical or procedural terms. Potential psychological, developmental, or identity-related harms associated with sustained self-monitoring are not substantively examined within this review model.

Because applied behavior analysis does not obligate its practitioners to examine the underlying reasons for behavior, the discipline lacks an internal standard for evaluating psychological risk or human benefit. Behavior is treated as an object to be modified rather than as an expression of developmental, emotional, or contextual need. As a result, risk assessment is limited to procedural safety, and benefit is inferred from observable compliance rather than from meaningful change in the child’s experience. Within this framework, autistic children are evaluated only in terms of behavioral output, leaving no disciplinary mechanism to assess whether an intervention supports or undermines their development, autonomy, or well-being.

An IRB may consider how Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) vocabulary plays a central role in shaping how interventions are ethically interpreted. Terms such as self-management, independence, treatment integrity, and social validity present surveillance-oriented practices as neutral, beneficial, or empowering. This language can function as a protective buffer, framing intensive monitoring as supportive instruction rather than as a form of behavioral control. In this way, ethical clearance signals disciplinary legitimacy more than it guarantees substantive protection for participating children.

The Core Verdict

Moore’s study demonstrates the operational continuity of behaviorist measurement practices and the institutional efficiency of compliance-oriented systems. It shows how behavioral monitoring can be transferred from trained professionals to students themselves, producing reliable documentation while minimizing demands on staff time and school resources.

What the study does not demonstrate is the provision of substantive, child-centered behavioral support. The intervention prioritizes data production, rater agreement, and procedural fidelity over skill development, emotional well-being, environmental adaptation, or meaningful engagement with students’ lived experience. Improvement is primarily defined in terms of correspondence with adult-defined scoring criteria rather than in terms of developmental growth or enhanced educational opportunity.

In this sense, the legal requirements of IDEA are procedurally satisfied: behavior is monitored, interventions are documented, and progress is recorded in measurable terms. However, the broader purpose of IDEA—to ensure meaningful, individualized support that prepares students for learning, independence, and participation in community life—is only partially fulfilled.

Jessica Moore’s dissertation illustrates how educational systems can demonstrate evidence of care without necessarily providing care itself.

Read this dissertation: Moore, J. L. (2019). An Evaluation of the Individualized Behavior Rating Scale Tool (IBRST) in Inclusive Classroom Settings. University of South Florida.

Leave a comment